History of change

PISARZOWSKI FAMILY: 16th – 19th century

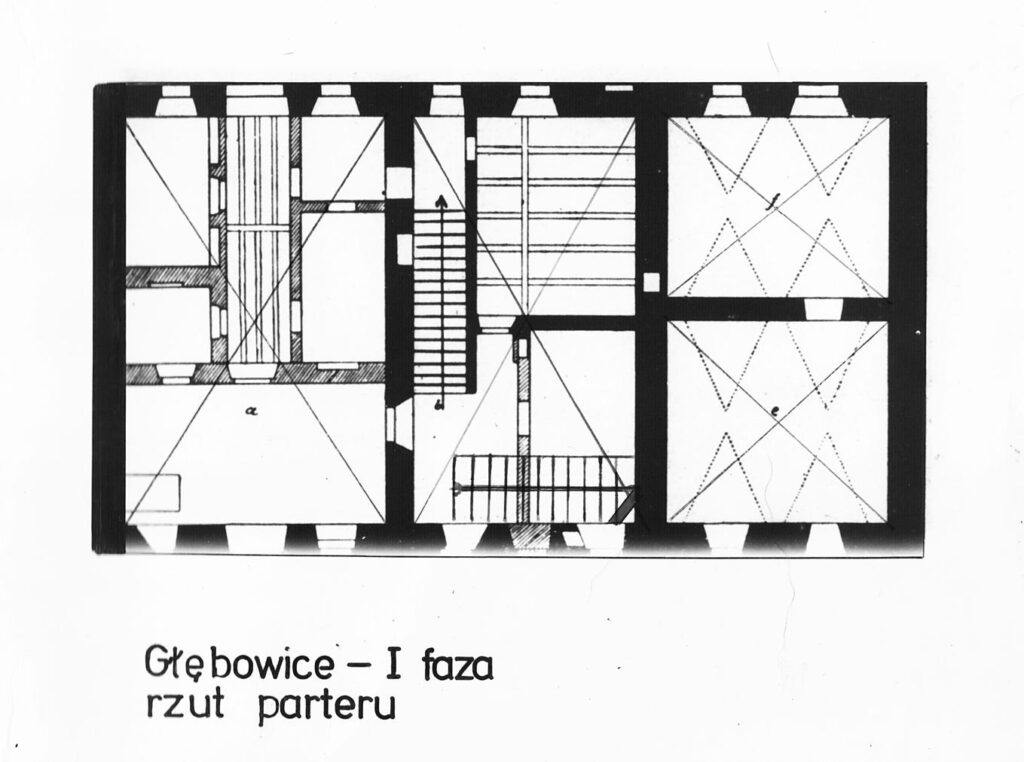

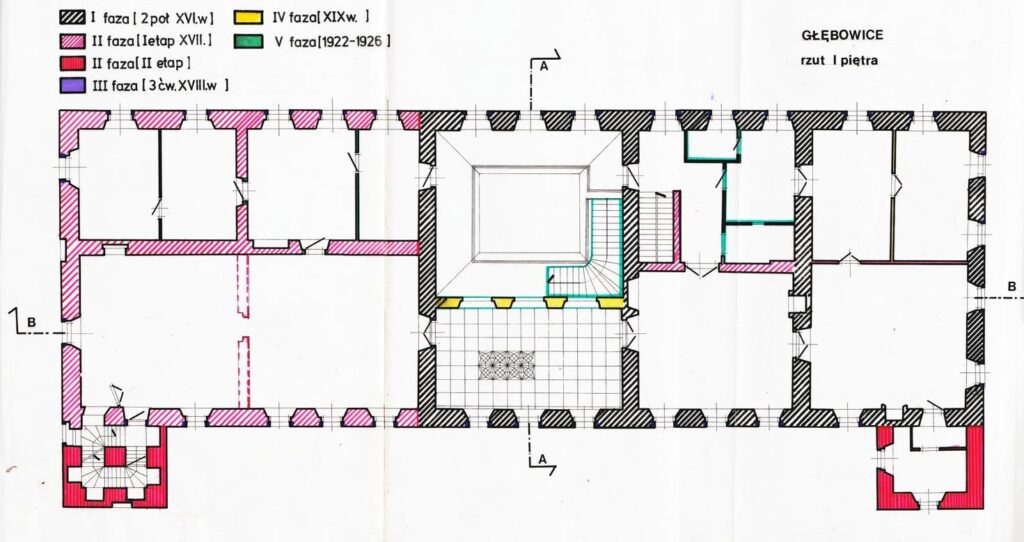

The grand Renaissance-Baroque Głębowice palace, despite its consistent appearance, was the result of multiple transformations. Originally a towered manor surrounded by a moat built in the 16th century, likely on the site of a defensive castle, it encompassed today's eastern part of the palace along with the foyer.

In 1646, Jan Pisarzowski expanded the building, extending it westward in a rectangular shape and likely fully cellarizing it. It is possible that initially a two-axis, cellarized independent two-story building was erected, which was later connected to the rest of the structure. The stone portals, wooden, beamed ceilings and polychromies created a Renaissance character inside the building.

This expansion was confirmed by traces discovered during the latest restoration of the building in the years 1922-1926, when the removal of plaster revealed old wall joints, remnants of original plastering and the outlines of two bricked-up windows.

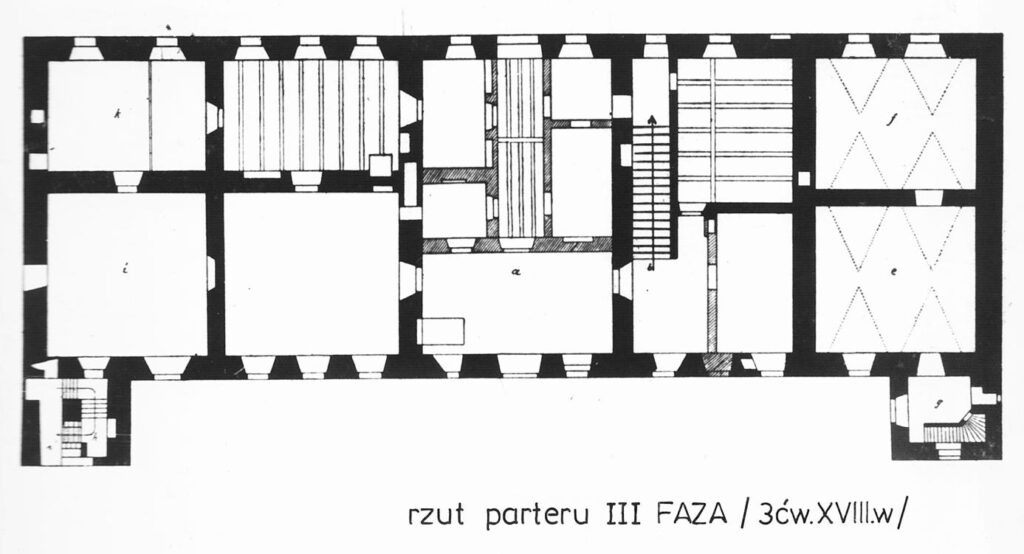

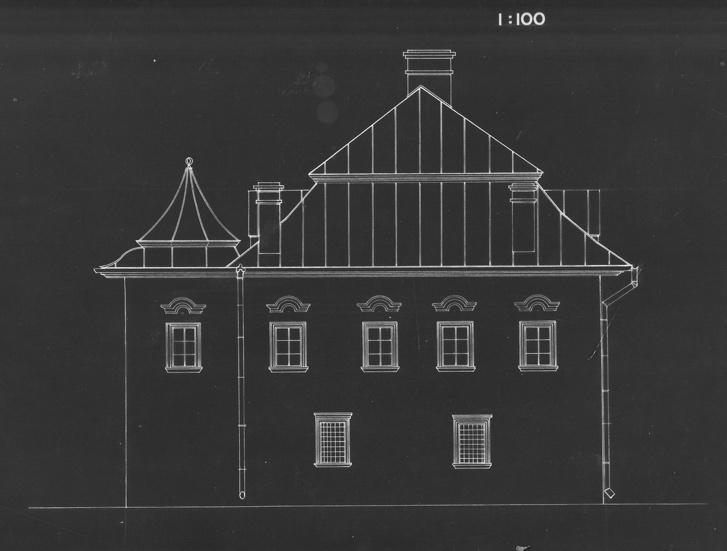

In 1773, during Adam Pisarzowski's time, two quadrilateral corner towers (risalits) were added to the palace, enclosing the front (southern) facade. The towers were topped with broken, conical Chinese-style roofs, lower than the main roof. A mansard roof, known as the French style, was placed over the entire building, from which waved, three-leaf gables emerged on the axes of both facades - front and garden - as well as dormer windows from the south.

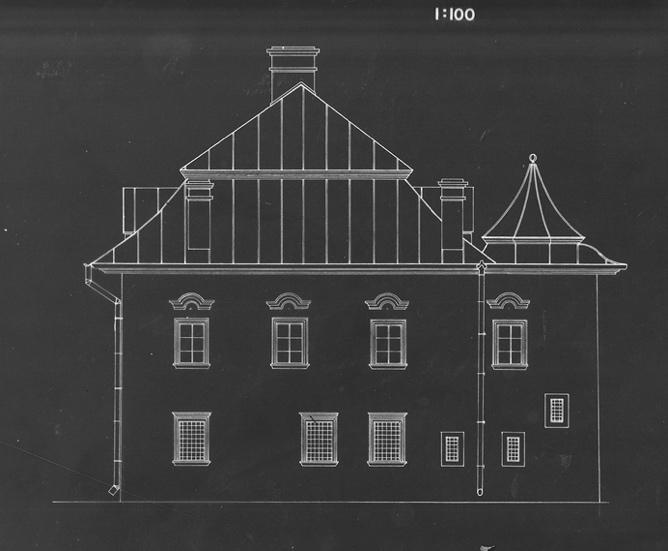

The roof of the western tower.

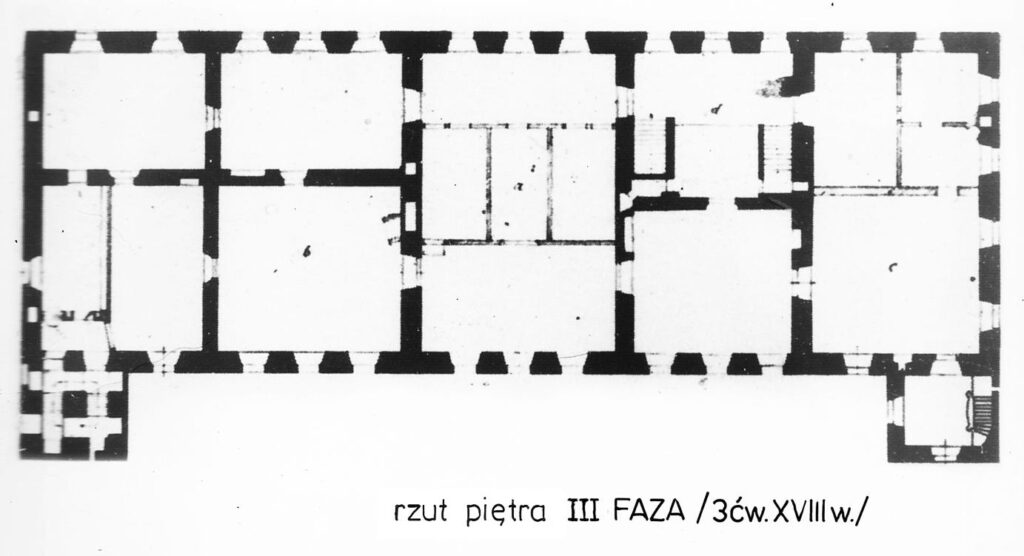

Above the windows of the first floor, profiled brick and mortar cornices were placed and the window openings were standardized by chiseling new frames for the ground floor windows and creating mortar bands on the upper floor. The grand hall in the eastern part of the floor was divided into three smaller chambers and the interior furnishings were altered, including the construction of new stoves and fireplaces, as well as the addition of paneling and new polychromes in the form of friezes with plant vines and oval medallions in some rooms. The entire building was plastered and the main entrance was moved to the center of the southern facade (where it is currently located), adding a second entrance from the north straight through.

When it came to furnishing and decorating the interiors by Adam Pisarzowski, the large chambers of Głębowice castle were adorned in an old-fashioned style. Furniture was imported from Gdańsk because it was the only one which adorned and supplied all the noble courts and lords' palaces (…)

In the first room, known as the crimson room due to its color scheme, a large mirror with frames adorned in golden roses with leaf garlands hung on the central wall. Below it stood a sofa, in front of which was a round table covered with a patterned carpet and a row of chairs placed around the walls completed the room's furnishings.

In the second room, called the yellow room, there were two mirrors in mirrored frames with different designs and shapes, along with a sofa and chairs with high backs and carved armrests, white lacquered and upholstered in yellow leather embossed with golden flowers, tied at the bottom in a cross, also intricately carved. The chairs in the first room were similarly upholstered and of the same shape, only instead of yellow leather, they had crimson leather with silver flowers. Cabinets, chests of drawers with convex sides, were lined with various designs of colored wood and mother-of-pearl and had gilded handles and porcelain medallions with miniatures near the drawers.

The restaurant and furnishing of the palace were linked to the work on its immediate surroundings. Pisarzowski created an Italian-style park around the building, covering an area of approximately 6.8 hectares, with about 1.5 hectares occupied by ponds. On the northern side, a geometric garden was created on two regular, rectangular terraces, bordered by hornbeam alleys, with additional embankments on the lower terrace from the east and west. Originally, there were two wooden pavilions on the transverse axis of the garden.

A moat ran along the northern, eastern and western walls of the palace, while a third, artificially created terrace with a retaining wall extended in front of the southern facade. The eastern part of the park was occupied by a pond.

From the 18th-century tree population, only 2 oaks, 2 purple beech trees, a Japanese magnolia and pine trees have survived to the present day.

The reconstruction in 1773 gave the palace the style of a grand Renaissance-Baroque residence, but despite its representative character, the object still retained defensive features, such as a partially watered moat and earth fortifications like walled embankments.

DUNIN FAMILY: 19th – 20th century

The next transformations of the property took place in 1844-1846 and 1922-1926, during the time of the Dunin family. The renovations carried out at that time did not alter the building's structure but rather the interior layout, introducing secondary divisions of rooms.

In the 1840s, Tytus Dunin furnished, renovated and partially rebuilt the palace without, however, disturbing its original character.

In the first half of the 20th century, the last significant renovation of the building occurred. Józef Stanisław Dunin conducted a thorough modernization of the entire property, interior restoration and recreated the former Italian geometric garden.

He introduced elements of neo-Gothic style, giving the building the desired ancient appearance. Pointed arch frames appeared, including those of the main entrances, some beamed ceilings were covered with flat faceted ceilings and paneling was installed in some rooms. A library and a so-called Gothic room were created. Most window niches were reduced in size, new chimney ducts were built and a small lift shaft was introduced in the eastern risalit to serve meals from the kitchen on the ground floor to the dining room upstairs.

The hallway running through the entire width of the building was divided into a vestibule to the south and a hall to the north. The wooden ceiling in the northern part was removed, creating a two-story space with a winding staircase leading to the upper floor (before the renovation, access to the upper floor was through stairs in the eastern part of the palace or stairs in the risalits).

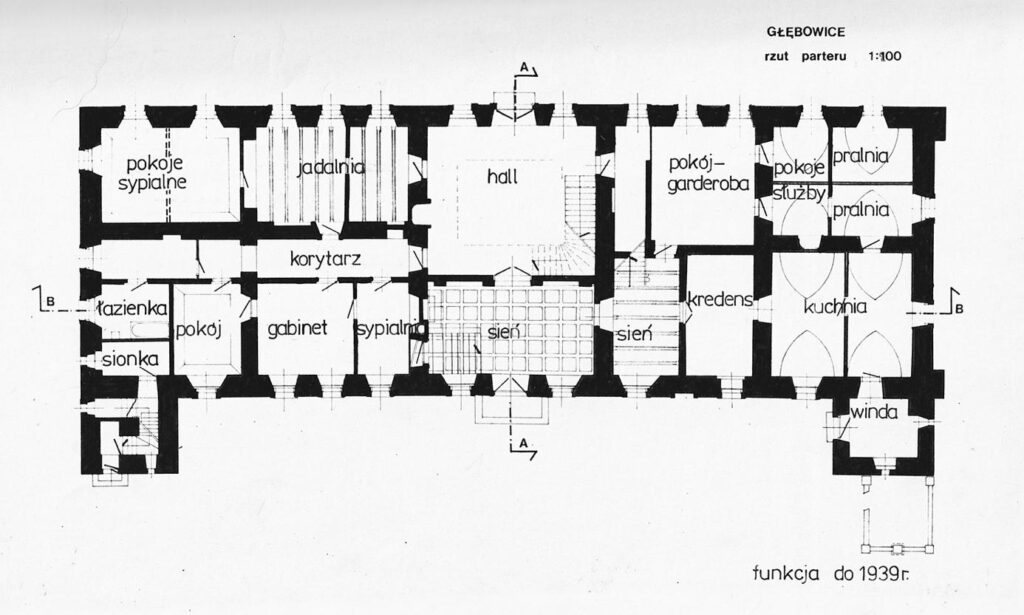

Originally, on both sides of the hallway, on both floors, there were four rooms arranged around the intersection of walls, connected by doors mostly placed centrally. Over time, due to internal divisions, more rooms were created and after renovations in the 19th and 20th centuries, in the last phase of the palace's existence, there were 18 rooms on the ground floor, 16 on the upper floor and 4 in the cellars. The central corridor was also created along the entire length of the western part of the building at that time.

Transformation phases from the 16th to the 20th century

WORLD WAR II

By the beginning of 1940, German authorities established an agricultural school and a summer headquarters for the Hitler Youth organization in the Głębowice estate. The occupiers immediately began adapting the palace for these new purposes, demolishing several original walls and rebuilding them elsewhere. They demolished, for instance, the partition walls on the ground floor between the dining room and the study, as well as on the upper floor between the Gothic room and the library.

POST-WAR PERIOD

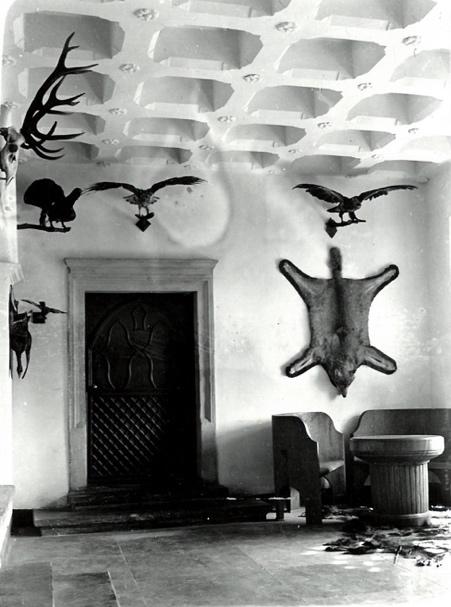

After 1945, further transformations of the building's interior took place when the estate came under the management of the Breeding Center in Osiek. The palace rooms were converted into apartments for workers, offices, warehouses, a canteen, as well as a hatchery and chicken breeding facility. Many new partition walls were erected during this time, including dividing rooms with mirrored ceilings and the red salon with a beautiful, multi-faceted, stuccoed vaulted ceiling.

In 1969, a fire broke out in the palace. The flames quickly spread from the eastern part to the roof, attic, turrets, first-floor rooms and staircase. The first floor was completely destroyed by fire, with only parts of the ground floor surviving.

The Regional Conservator of Monuments covered the remaining ruins of the palace with a flat, makeshift roof, which, left without conservation, quickly collapsed. Since then, due to a lack of proper protection, the remnants of the building have been systematically deteriorating.

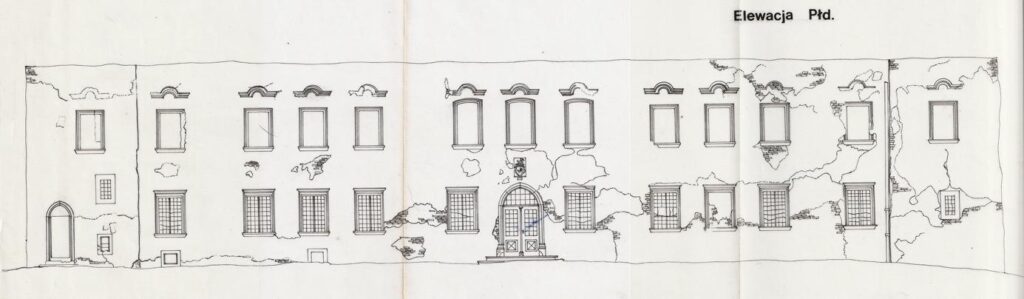

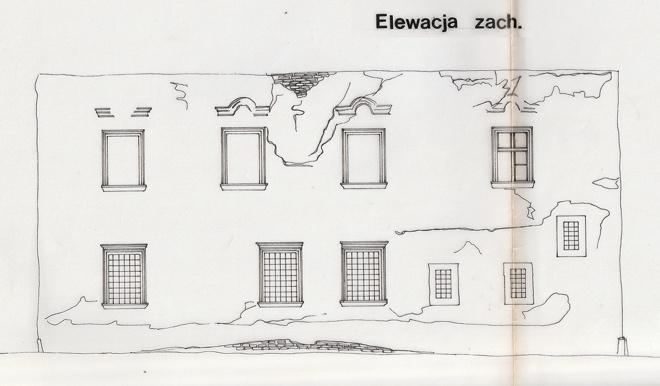

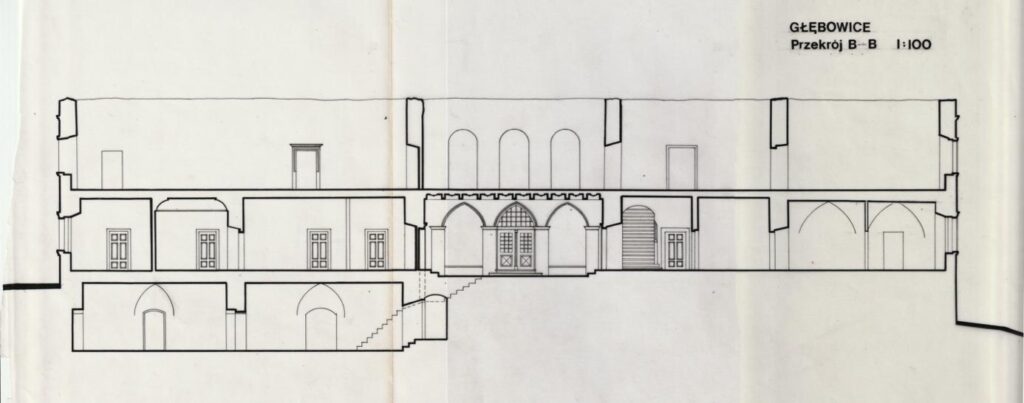

1975r.

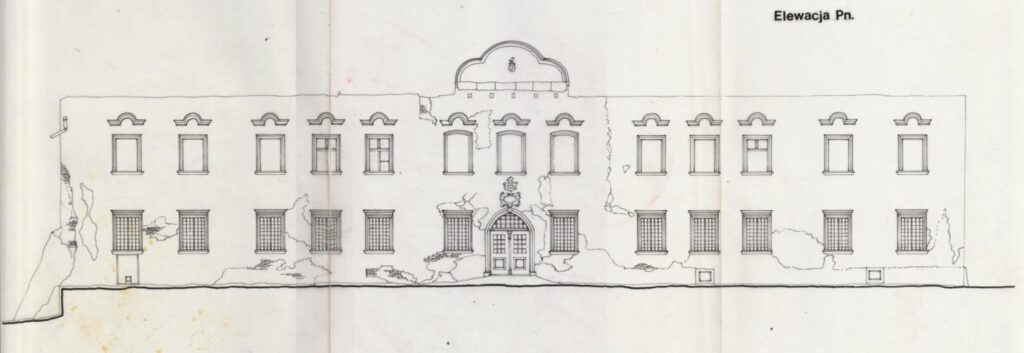

The north facade, 1975.

The south facade, 1975.

West facade, 1975.

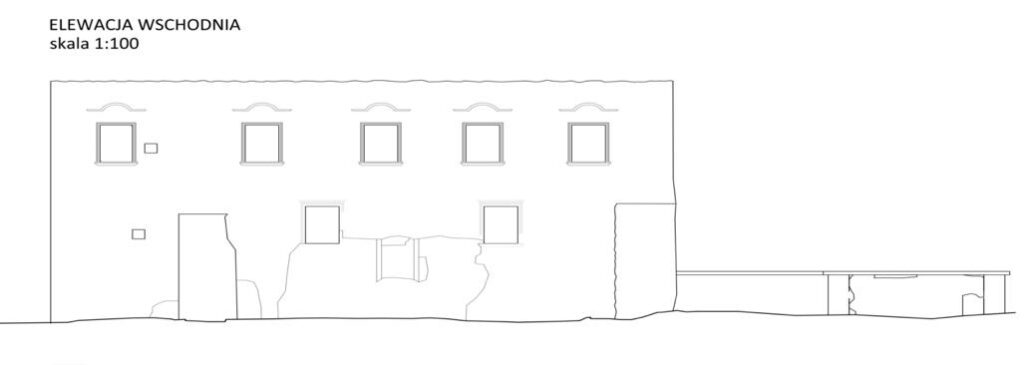

East facade, 1975.

North section, 1975.

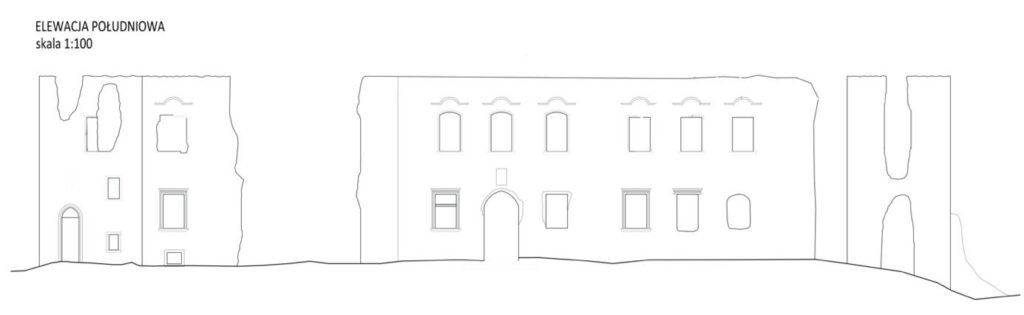

2019r.

The north facade, scale 1:100

The south facade, scale 1:100

The west facade, scale 1:100

The east facade, scale 1:100

Palace in 1939r.

GŁĘBOWICE ESTATE

The Głębowice Palace, recognized in 1937 as a first-class historic landmark, was among the most magnificent rural residences in the Kraków region during the interwar period.

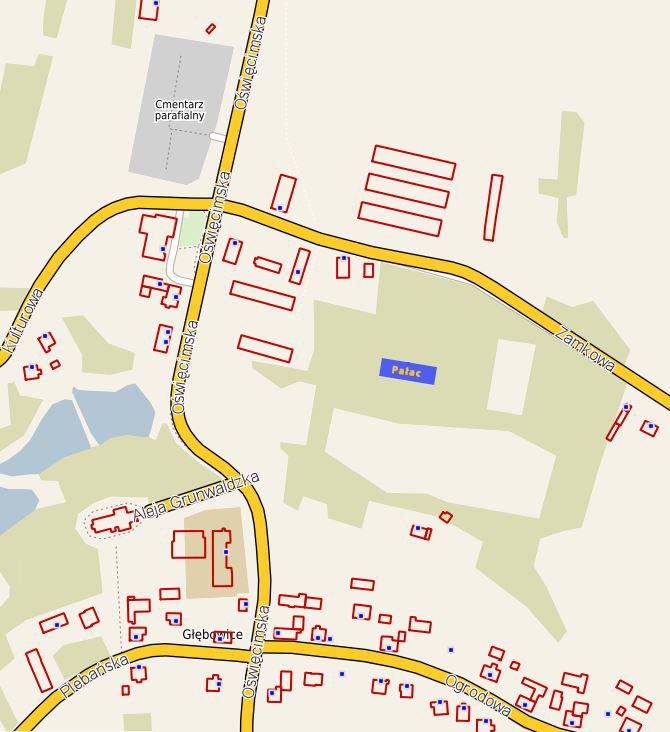

Situated in the northeastern part of the village of Głębowice, the estate is nestled on a gentle rise sloping southward towards a pond.

Map of the village of Głębowice.

The palace, along with the park, surrounded by a fence, constituted a separate unit from the rest of the estate, unrelated to agricultural or livestock production. The natural separation of the palace was also provided by the moat. The area with farm buildings was separated from the park and palace by a road.

The palace from the north-west side with the entrance to the courtyard, 1939.

The farmstead complex, whose spatial layout has survived to the present day, consisted of agricultural, storage, and residential buildings (including a quadrangle from the early 20th century and a steward's house from the 19th century), a barn, a calf shed, a pigsty, two barns from the first half of the 19th century, and three stables - two from the mid-19th century (one of them still bears the Swan coat of arms), and one from the 20th century used as a workshop and fertilizer storage. The buildings were constructed of brick and covered with a gable roof made of ceramic tiles.

The farmstead complex bordered the palace to the east, and to the south, it was bordered by the Browarnik pond, on the bank of which a statue of St. John of Nepomuk was placed. On the northern side, the second part of the agricultural buildings was situated, beyond which stretched the agricultural lands of the estate.

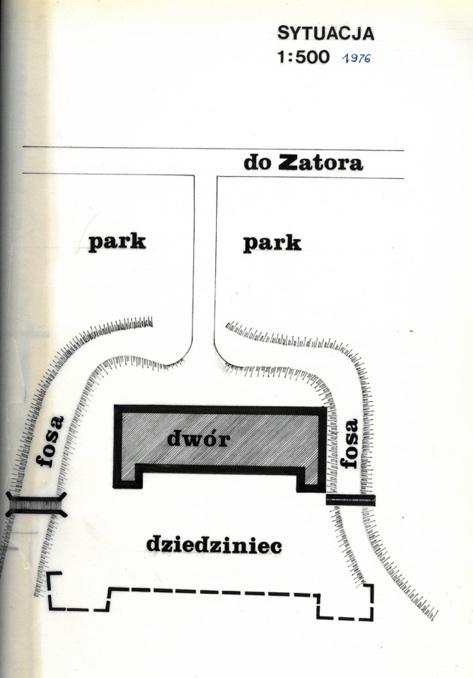

From the side of the farm buildings, a road ran through a stone bridge to the courtyard of the palace in front of its southern facade. The courtyard was bounded by a brick wall with two square projections facing the pond. The immediate surroundings of the palace were artificially leveled and enclosed in a rectangle measuring 44x46 meters. To the north, east, and west, the palace was surrounded by a moat with a cobbled inner bank.

The palace with ponds and a part of the farmstead including residential and agricultural buildings, barns, and stables, 1937.

Situational map, 1976.

The palace with the castle pond, a part of the farmstead, and the road leading to the courtyard, 1937.

Entrance to the palace courtyard through a stone bridge from the west side, 1939.

The palace is oriented towards the south, freestanding, single-story building with an attic, partially basemented in the western part. It was constructed of brick, using stone in the foundation zone, and plastered. Built on the plan of an elongated rectangle with two square projections on the front side, which, however, do not protrude beyond the line of both side walls of the building. Smooth, vertical facades were crowned with a cornice hidden under the roof overhang.

The north facade

The south facade

In the central part of the north and south facades, there were pointed-arch, main entrances, narrowly and modestly profiled in the plaster. Above the entrance on the north side, a foundation plaque commemorating the reconstruction in 1646 was embedded, and on the south side, the Swan coat of arms of the Dunin family was placed on a shield topped with a count's coronet. The coat of arms was also positioned on the north side, on a three-leaf element projecting from the roof's peak.

Fragment of the northern facade with a gate featuring antefixes in the shape of lion heads and with a foundation plaque with a heraldic shield from 1646. Photo from 1961.

Gate from the southern side with the Swan coat of arms on a shield crowned with a count's crown. Photo after the fire in 1969.

Symmetrically arranged, equally sized ground floor windows (except for the risalits) had modest stone frames with a Renaissance profile, while the rest were from the 18th century. The ground floor windows were topped with a delicate cornice, and above them on the upper floor were lintels with a gently curved line.

Ground floor window

Windows on the first floor

INTERIOR OF THE PALACE

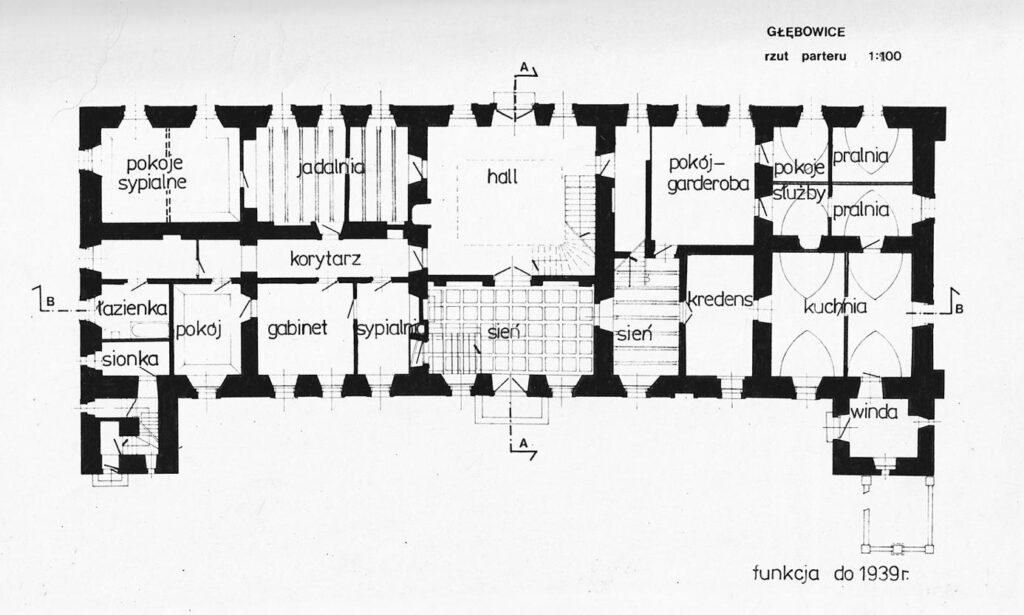

Ground floor

On the ground floor, the central part of the building was occupied by a divided vestibule, spanning its entire width and featuring two entrances from the outside. Its southern part was a vestibule, corresponding to the red salon on the upper level. The northern part was taken up by a two-story hall with stairs leading to the upper floor. In the partition wall separating the vestibule from the hall, there was an ogival passage, enlivened on both sides by similar ogival blendings of the same height. In the western part of the vestibule, there was an entrance to the cellars, and in the side walls - symmetrical passages to the side rooms of the palace. The vestibule was covered by a stuccoed, coffered ceiling with rosettes.

The vestibule of the stone hall from the front entrance (southern), with an entrance to the hall and stone portals from the 16th century.

In the photo on the right, benches and a millennium table carved from a single oak by carpenter Saferna in 1930. Photo from 1939.

Stone portals were placed in the eastern and western walls of the hall, leading to side rooms. Along the western wall, between the doors, there was a sandstone fireplace. Along the eastern and southern walls ran ornate stairs to the upper floor. The exit on the northern wall led to the garden.

The northern part of the vestibule (hall), with winding stairs leading to the upper floor

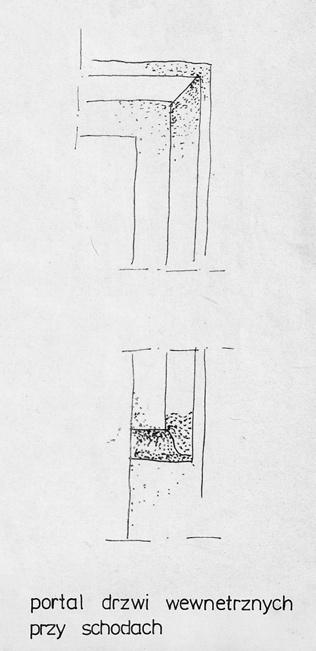

The portal of the internal doors near the stairs.

The internal portal in the hall.

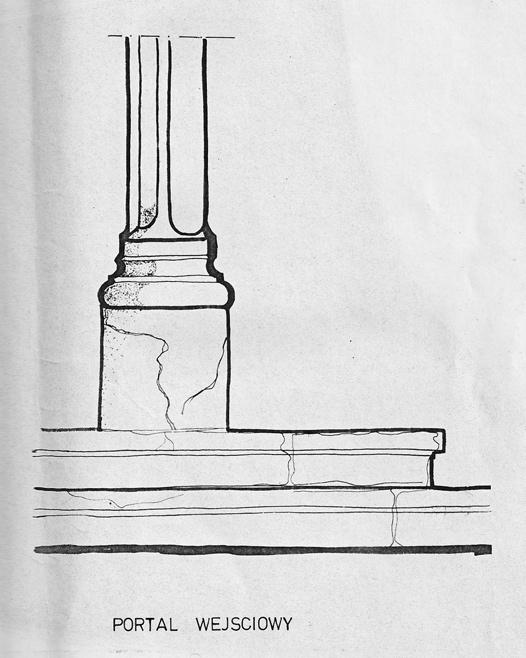

The entrance portal.

In the western part of the ground floor, there was a secondary corridor connecting the rooms with the hall, one of which had a mirrored ceiling. The rest of the ground floor rooms were covered with ornate ceilings or wooden beam ceilings, except for the two oldest, extreme eastern ones, crowned with barrel vaults with lunettes. These two rooms also had lower floor levels compared to the rest of the building.

Depending on the room's function, the floors were either stone with marble slabs, brick floors, or wooden parquet.

In the western risalit, there was a staircase with winding steps around a pillar, with landings, while in the eastern part, there was a small elevator for transporting meals from the kitchen to the dining room on the upper floor. Another staircase led to the upper floor from the eastern part of the palace, just behind the northeastern wall of the hall.

Ground floor plan, 1939.

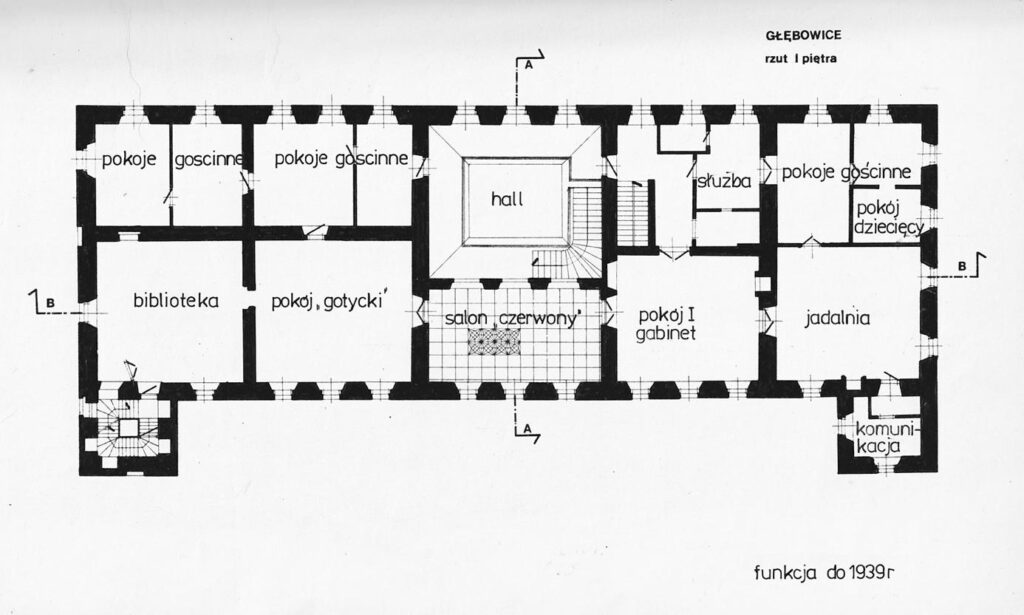

First floor

The main stairs in the hall connected to the gallery on the upper floor, encircling horizontally the upper part of the hall with entrances to the eastern and western parts of the palace. The central, southern part of the bel-étage was occupied by the so-called red salon, with a beautiful multi-planar, stucco ceiling. The red salon was separated from the gallery by a wall pierced with three semi-circular arches.

The red salon, 1928.

Behind the red salon, the gothic room, 1939.

The study, 1928.

The first floor essentially had the same layout as the ground floor, but slightly more symmetrical and with fewer partition walls and dividers. On both sides of the gallery and the red salon, there were rooms, but on the southern side, they were not divided like on the ground floor, but rather two large rooms on each side, forming a long enfilade extending across the entire front section of the floor.

First-floor plan, 1939.

The eastern rooms on the upper floor were finished in an eighteenth-century style – fireplaces with stucco frames, modest, low wainscoting, wooden doors with downward-curved lintels. The rooms were covered with mirrored ceilings with facets or smooth and beamed vaults, and the floors were paved with parquet made of planks from various types of wood, arranged in geometric mosaics.

Fireplace on the first-floor

From the earlier decorations, in the western part of the palace, stone jambs with a Renaissance profile have been preserved. After the fire in 1969, some burnt rooms revealed previously unknown Renaissance polychromes with floral motifs hidden beneath the plaster.

Uncovered after the 1969 fire, previously unknown Renaissance polychromes.

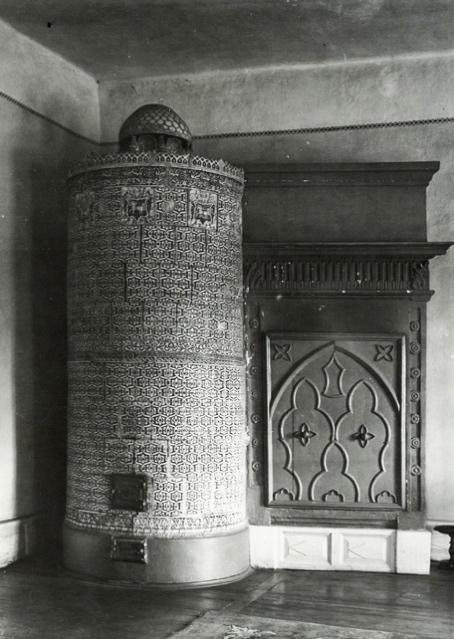

Most likely in the gothic room, next to the red salon, stood an oval, Baroque tiled stove installed by Jan Pisarzowski during the reconstruction in 1647.

The stove was mainly constructed from decorative tiles with a slightly raised, white pattern of ornamentation on a blue-navy background. In its upper part, larger tiles with shields containing the Pisarzowski Starykoń coat of arms, the letters J.P.Z.P.Z.O.Z.P. (which are supposed to stand for: Jan Pisarzowski from Pisarzów in the Oświęcim and Zator Land Writers), and the year 1647 were rhythmically arranged. The base of the stove rose in a two-story structure separated by a small offset, adorned at the top with a narrow crown with a richly decorated cornice. The stove was capped with a domed roof, supported by a cylindrical body, surrounded by eight pillars widening towards the bottom. The roof and pillars were covered with a drawn scale in the background color of the tiles, blue-navy.

Baroque tiled stove from 1647, next to the fireplace. Głębowice 1939.

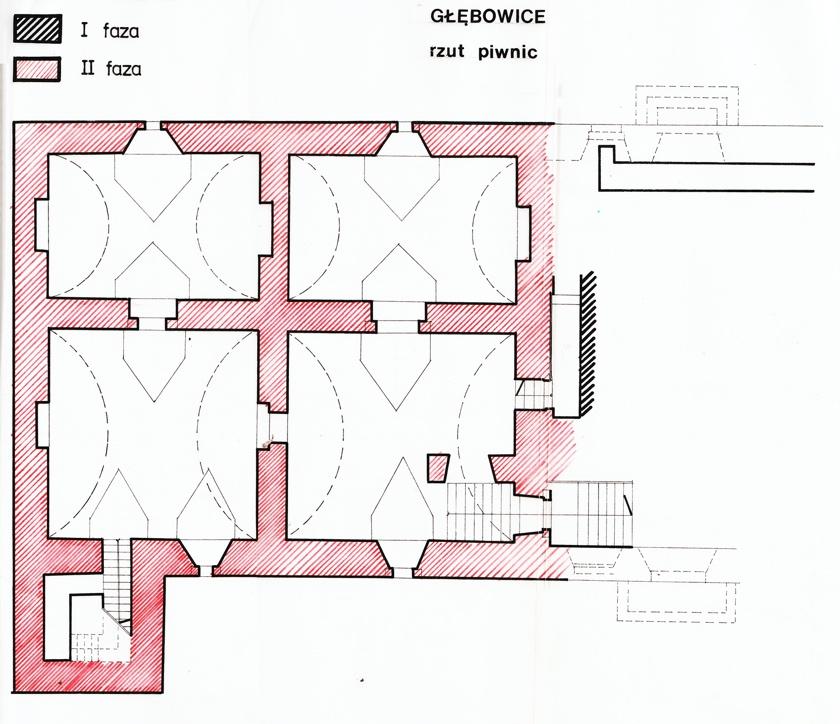

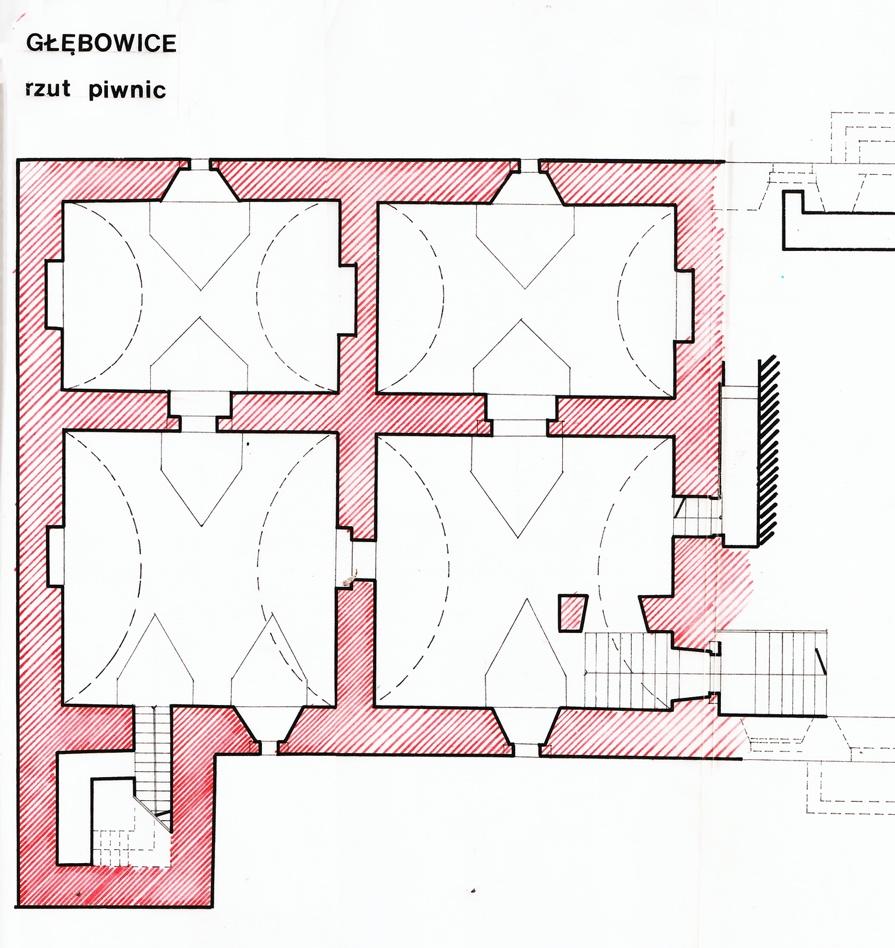

Cellars

During the interwar period, only the cellars under the western part of the palace were accessible and used, forming a regular complex of four rooms. They had stone-brick barrel vaults, and their rectangular windows were just above ground level on the north and south sides. The remaining cellars were likely filled in, and it's possible that there were no cellars at all under the eastern rooms. Stairs leading to the cellars were located in the vestibule, on the left side from the front, southern entrance, with another set in the corridor of the western wing.

Stone stairs from the vestibule to the cellars, 1939.

Cellars plan, 1939.